Related

Honeyman

This is a story about one of the business people I interacted with in my early years as an SEO consultant and web developer. This anecdote...

07 min reading in—Anecdotes

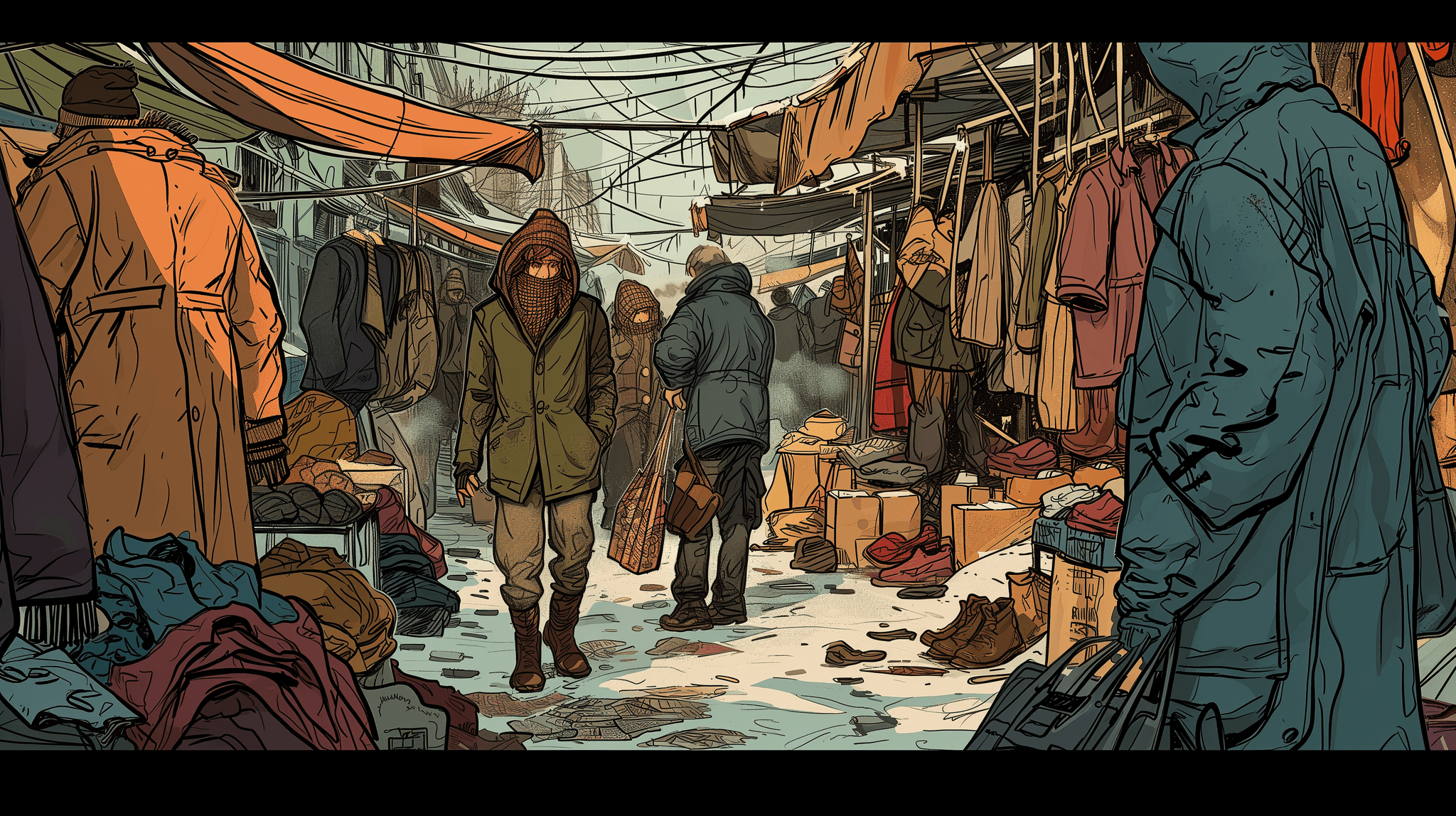

Dive into my journey through the bustling marketplaces on the outskirts of Moscow in 'The Bazaar.' In this narrative, I reveal the vibrant world of post-Soviet trade hubs, where cultural legacy intertwines with the echoes of a bygone era.

I was involved in the knock-off shoes and garments e-shop during my early entrepreneurial days. That's how I learned about those bazaars on Moscow's outskirts. It was an interesting marvel of the time, presenting a rich cultural background. I'd like to say that it came and went, and now it's not there any more, but as far as I know, those trade syndicates still exist and thrive.

The source of our website's product portfolio was not just any place, it was something truly remarkable: an iconic landmark in every post-soviet city of the time, a mother and a father of all malls, a place where fortunes were made and deals were done.

It looked like a flea market or more like a Turkish bazaar in a post-apocalyptic setting, filled with all kinds of textile and leather products you can think of imported from China, Turkey or other countries. Some bazaars were open for retail customers, and others were mostly for wholesale.

Those bazaars came to life in the late 80s, when the first freedoms were granted and yesterday's felons became the first merchants (all commerce activities were considered a felony in the USSR). There were known 'places' where you could meet those felons: you hang out on the spot, then someone wearing Western outfits would casually pass you by, and you murmur something you would like to get: jeans, watches or a bottle of perfume. Those places where these acts of petty treacherous were committed later became flea markets and, in some years, unregulated trade fortresses as they are today.

At first, people stood and sat near their goods on the pavement. Later, some makeshift structures arose: shipping containers were placed, and some booths were built. The places were bustling with people, as that was the only chance for anyone in the nineties to get something to cover themselves with.

Being a kid at the time of the rise of these markets, I remember my experience coming there to get a pair of jeans or a shirt: it's a murky place where you have to shoulder your way following your mother. You go from one shipping container to the other, trying on the jeans or whatever it is. Once you get your size, you are stood on a piece of cardboard, and some lady is holding a curtain so that your miserable, pantless attempts to balance yourself will not be exposed to the crowd. The trick is to stay on the cardboard, as the ground is covered with mushy snow colour of dirt.

The government tried to control the trade, but the best they achieved was to contain the activities, moving it further and further from the centre.

As the years rolled by and the Moscow public grew more affluent and discerning, the bazaars demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability. Shifting from their traditional offerings, they now specialise in knock-off goods and wholesale trading, catering to merchants from distant cities such as Murmansk and Grozny, becoming regional hubs for international trade.

These bazaars were a melting pot of cultures, with several primarily Chinese bazaars, at least two Vietnamese and one Azerbaijani. Controlled by prominent Mountain Jewish and Chechen families, each bazaar had its own leadership, security, hierarchy, banks and cultural imprint. They were more than just trade centres. They were vibrant ethnic enclaves, offering authentic cuisine, barbershops and drugstores for the locals.

The biggest market is called 'Moskva'. I just checked, and it still exists and is thriving as of 2024. It is located beside the outmost of Moscow's ring roads, between residential blocks and an industrial zone. It is a massive structure that is hard to circuit: many buildings, a vast parking area, and some heavily guarded storage areas. Armed security patrolling the aisles. It is a place to trade as much as a place to live, as many do not leave the premises and stay there for the night, sleeping in several hostels in the area.

The bazaar presents an enclave with checkpoints, 'police', 'banks', and even its own justice system! Black market financial services and things like drugs and prostitution are available to the locals.

The society of the bazaar features social groups with distinct ethnic characteristics. So, it's an easy guess that someone from China is a trader, while a person from Tajikistan is probably a boxman.

A peculiar fact is that the owners of this trading hub are known to be Mountain Jews, a small and unique community of Jewish people of Persian descent originating from the North Caucasus.

So, the social ladder that you can't climb looks like this:

Shipping and 'customs clearance' are among the most important parts of the bazaar's economy. Most of the goods that are sold there bypass customs in this way or another. Every major trade route between Russia, Kazakhstan and China had its own 'perks': somewhere you could squeeze in a full container without the duties paid, and somewhere you could 'import' a crate or even a single box.

The smuggling is a well-documented and established grey area of Russian-Chinese relations. Smugglers are primarily Chinese nationals. They deal with transporting goods and money so that a bazaar shop owner can bring cash, get it wired to his Chinese bank or WeChat account, and receive the goods, avoiding the hassles of customs clearance.

I got acquainted with a smuggler in China a few years after my repair shop business got up and running, and it's a whole other story!

Now, back to the market! Buses from around the European part of Russia arrive as early as 4 AM at the large parking lots outside the bazaar. They are met by trade agents and boxmen looking to be hired for the whole morning. The shops are already open and waiting for their wholesale customers.

Passengers, primarily ladies in their fifties and sixties, are slowly getting dressed and emerge on the parking lot. They journeyed through the night from their hometowns to restock their stores. Most buses feature some kind of makeshift sleeping bunks, running water, and a toilet, giving the impression of a variety of steampunk camper vans.

Imagine it's a dark winter night, it's -20 c˚ outside, and you are making a routine visit to the capital to restock your shops with cheap boots, parkas, and pantaloons fit for the Russian winter. You don't see much of the city: it's dark now, and by 8 or 9 AM, it will still be dark when you leave.

The plan is the following: you need to hire a boxman with a large cart. He will follow you all morning on your visit with his cart. Your job is to point your finger at the things you like for your store and order several size runs. The goods are piling on your man's cart, labelled with your name, bus destination, and license plate (Let's say it is Ira - Vologda - A 556 BT). You pay for the goods in cash, forking out the bills from the thick roll, and wind your way to the next shop, some hundred meters away.

Your boxman has to go back and forth a few times, dropping your goods at the bus. He is an energetic gentleman of the same age as you, coming from Tajikistan and working for you every time you arrive. He must be trusted, so you don't hire younger folks who speak very little Russian. Your helper, whose name is Rustam, has a degree in history and used to be a teacher back in the days of Gorbachev, the same degree and occupation you had! So, you work as a pair for a few hours: he's handling the goods, and you're dealing with the money.

After the trade is done, you still have an hour or so left. You sit with Rustam in the Uighur joint, consuming the steaming noodles with some unknown meat, casually talking about families and crooked Chinese shopkeepers. You pay for the early lunch, hand Rustam his day wage, about 2000 or 3000 rubles (around 30 or 50 bucks), and part.

You board the bus, get back to your bunk and try to make up for the lack of sleep this morning. The next day, you will spend looking at the endless white fields, small towns and gas stations, waking up and slipping back into your dreams. With a few stops on the way for a snack and an actual toilet, you're back home at around 7 PM.

Now, imagine this is your routine for the last 20 years. Sometimes you do it bi-weekly, sometimes every week, and sometimes you ask your husband to go instead of you, but he always brings something you don't like, so you prefer to do it yourself. Your children used to admire your trips when they were smaller, as it was easy to please them with toys and fancy garments, but now they have grown up, and it seems like they are a little ashamed of your routine.

Do you remember when you used to be a teacher? It was over twenty years ago. You taught children about a country that no longer exists. Some of the stories you told them were true, while others were fake, made up by the communists. Rustam did the same on the other side of the empire, but now no one remembers any of it - not you, your students, or even Rustam.

Today's bazaars are filled with a new generation, distinct from the first wave of post-Soviet traders. They're savvy, quick, and understand the unspoken rules of this world. Many from the far reaches of the former Soviet Union see this life as a stepping stone, hoping to establish businesses eventually.

Characters like The Trade Lady and Rustam are now less common. They represent a generation with unfulfilled dreams, uprooted from planned engineering, teaching, or manufacturing careers. The collapse of the Soviet Union forced an entire generation into an involuntary shift, a sort of emigration, trading their professions for market stalls, meeting harsh realities of wild capitalism in the murky setting of former soviet cities.

I am surviving my own 'real' emigration: a new home and a new language. I am now finishing my first decade outside of the familiar culture. After Russia went to war with Ukraine, I realised that my friends who chose to remain in Russia became non-voluntary immigrants, exactly like their parents.

Russian society, longing for the certainties of the Soviet Union, embraced the shift to fewer freedoms and opportunities as if the rest of the Soviet 'perks,' like clear career paths and accessible housing, would follow. I see how hard it is for my generation in Russia now, but for our parents' generation, that was ten times harder, and I try to remind myself of that every time I want to whimper.

This is a part of my Crazy CV series. If you like to read similar stories, please check it out!

Related

This is a story about one of the business people I interacted with in my early years as an SEO consultant and web developer. This anecdote...

Related

Years active: 2005 - 2011. Role description: Co-founder of an innovative e-commerce venture specialising in fashion retail.

Related

Years active: 2002 - 2007. Role description: Freelance web development and SEO consulting